Mumbai’s waterlogged streets have become an annual monsoon feature, bringing to the fore flaws in the city’s planning, yet warning signs continue to be ignored.

Shrinking wetlands, encroached mangroves, deterioration of riverine systems and mindless concretisation which leaves little space for water to percolate into the ground — this makes Mumbai a perfect case for waterlogging during heavy rainfall.

The August 29 flooding, which revived memories of the July 2005 deluge, was another example of weather vagaries combining with urban chaos, bureaucratic mismanagement, and destruction of a fragile ecosystem to bring the country’s financial capital to a standstill.

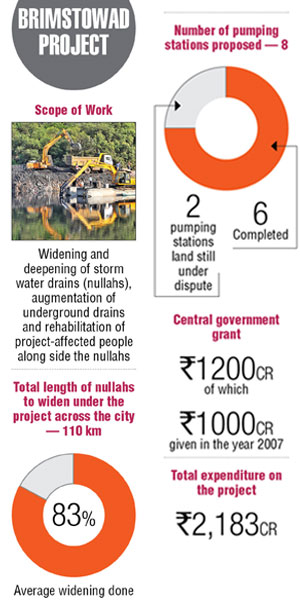

After the 26/7 deluge, the state government set up a fact-finding committee under former union water resources secretary Madhavrao Chitale. The committee sought that the 1993 Brihanmumbai Storm Water Drainage (BRIMSTOWAD) report, which suggests measures to prevent flooding by augmenting the almost century-old storm water drainage, be taken up on an immediate basis.

However, like the clean-up of the Mithi river which flooded its banks in 2005 wreaking havoc, the BRIMSTOWAD too remains far from complete, its implementation mired in political apathy, red-tape and encroachments.

While many policy initiatives have focused on Mithi, little attention has been paid to the three other rivers flowing through the city — Oshiwara, Poisar and Dahisar.

“Mumbai’s capacity to absorb excess rains is limited,” noted BC Khatua, project director of the state government think tank Mumbai Transformation Support Unit (MTSU). He added that many areas in the city, created through reclamations, were lower than the mean sea level, leading to waterlogging.

“There is limited space for water to percolate the ground. There are four rivers and 19 nullahs in the suburbs but they have been encroached upon and debris have been dumped, which impedes water flow,” explained Khatua.

A study commissioned by the MTSU and conducted by the National Institute of Oceanography, stated that Mumbai’s area has increased from 437.37 sq km in 1991 to 482 sq km now due to reclamations and years of silting by the sea. Land has been added largely on the eastern coast, with the western coast, which is exposed to stronger currents and winds, facing erosion.

The study, which examined the impact of reclamation over the past century, pointed to how indiscriminate reclamation has affected the fragile ecology and morphology of Mumbai. For instance, the embankment at Bandra for the Bandra-Worli Sea Link has eroded the Mahim-Dadar beach by affecting wave and current patterns.

“Since 2005, nothing has been done for the rejuvenation of rivers and removal of debris from the wetlands,” charged Gopal Jhaveri, founder, River March. He added that the 5,000 trucks of debris generated in the city daily were dumped on the wetlands, river beds, mangroves and highways.

Jhaveri said the tabelas around the Dahisar river dump cow dung and animal carcasses into it, which impedes the flow. He pointed to locations like Ganpat Patil Nagar in Dahisar, Malvani, Charkop, Juhu and Khar Danda as locations where mangroves were encroached upon.

The interim report on the study for flood mitigation measures for the Dahisar, Poisar and Oshiwara rivers by the Water and Power Consultancy Services (WAPCOS) in December 2005 states that developmental activity has caused a reduction of river width. Depths have reduced due to dumping of debris and siltation.

“The reasons laid down by the Chitale committee report remain valid,” noted Rakesh Kumar of the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI). “Simulated urban flood monitoring must be conducted and action must be taken,” Kumar stressed, adding that mangroves were increasing the creeks because of silting and reducing on the landward side due to encroachments. This led to the creek shrinking, thus affecting drainage.

Urban quagmire

A senior BMC official said while they were targeting a dispersal capacity of around 50 to 55 mm precipitation per hour for the city’s storm water drains under the BRIMSTOWAD project, it was just around 80 per cent now. “These drains were designed to handle water flows at 25 mm per hour but it’s tough to augment storm water lines near thickly-populated areas,” he admitted.

Interestingly, while the BRIMSTOWAD, which seeks to alleviate flooding in Mumbai city and the suburbs, was prepared in 1993, its implementation received a boost only after the 26/7 deluge.

It will cover refurbishment of century-old closed conduit storm water drains, widening, deepening and strengthening of nullahs in suburbs, and pumping stations. The costs have swollen from Rs 1,200 crore in 2005 to Rs 3,900 crore now.

The official said while 58 works were to be completed in two phases, the first arm is almost complete with around 75 per cent of the components in the second phase being covered. “Encroachments, delayed permissions from other authorities and land acquisition have caused the delay,” he added, admitting it was tough to state a deadline.

Deadly development

Debi Goenka of the Conservation Action Trust (CAT) said builder-led development without any concern for the environment had contributed to the state of affairs.

Few lessons learnt

D Stalin of NGO Vanashakti said natural drainage and dispersal systems had been affected, thus impacting dispersal of flood waters. Stalin noted that cutting of trees for projects like the Mumbai Metro would lead to more siltation and runoff into the rivers. He stressed on the need for a 100-year flood plain demarcation.

The around 35 lakes and over 1,000 wells in Mumbai which act as receptors of water have also been affected.

Threats

The Maharashtra Maritime Board’s (MMB) shoreline management plan (SMP) has suggested that constructions near the coast in Mumbai must rise to a minimum 7.59 meters above mean sea levels by 2050 to withstand storm surges and floods. It has predicted a 0.38-meter rise in sea levels across Maharashtra by then. During tides, there may be flooding in low-lying areas.

Solutions

With projects in the pipeline like the Marine Drive- Kandivali coastal road and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj statue in the Arabian Sea requiring reclamation, this calls for a cautious approach.

“Reclamation per se is not always against nature… but we have to study its impact on the neighbourhood,” urged Khatua, adding that holding ponds could be integrated into the coastal road design to serve as a sponge.

Kapil Gupta, Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology (Mumbai), noted that infrastructure improvements were needed. This included demarcating existing drainage systems, preventing encroachments on them, porous pavements to prevent water run-off, ensuring a common level of the road and plinth and storage of rainwater in tanks at the rooftop, intermediate, ground or underground levels to reduce flood volumes.

Jhaveri sought a debris management plan, a plastic management system and ban on plastic cups and straws and stressed on the need for mass housing projects or encroachment removal and urban renewal.

Land, land everywhere

Reclamation city

As Mumbai evolved from a collection of fishing villages to a vibrant metropolis, it has seen multiple waves of reclamation. This includes one of the first in the 1700s at Umerkhadi to control malaria, constructing the Colaba (1838) and Mahim-Sion causeways, building railways and the port and creating business districts like Ballard Estate and recently, the Bandra Kurla Complex.

Slums and housing projects also sprouted on reclaimed land. Later day reclamations include the controversial Backbay Reclamation project during the tenure of then chief minister Vasantrao Naik, Bandra and the Lokhandwala complex.

Reports & studies

Various committees and consultants appointed to study the flooding in Mumbai include: Natu committee (1975), report on model studies on the effect of proposed reclamation in Mahim Creek (Bandra-Kurla Complex) by the CWPRS (1978), Dharavi storm water drainage system (1988), BRIMSTOWAD (1993) and remedial measures to abate flooding at Milan Subway and Sleater Road (Grant Road)/Nana Chowk (2005) by IIT Powai.

Chitale committee’s proposed solutions

Restore existing degraded rivers and river banks to initiate recovery of the urban ecosystem, provide buffer zones with unpaved pathways

Rejuvenate degraded urban ecosystems including lakes/ponds, rivers, creeks, and costal zones

Restore mangroves and rejuvenate coastal zones

Rejuvenation and environmental upgradation of hills, slopes, and lakes/ ponds in Mumbai

Improve municipal solid waste (MSW) management as improper disposal chokes sewers and storm water drains